An Intersection of Spirituality and Humankind: A Review of Akwaeke Emezi’s Content Warning: Everything

By Ement Amaku

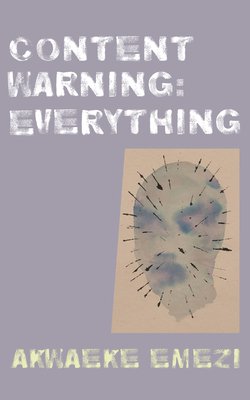

Akwaeke Emezi, the critically acclaimed author of the bone-chilling novel The Death of Vivek Oji, explores Igbo divinity and Christian mythology in their debut poetry collection, Content Warning: Everything. The speaker is embodied in the collection as Ọ̀gbánjé, an Igbo divine spirit who was once believed to be an evil spirit that deliberately plagues a family with misfortune; Ìdémmìlí, an Igbo mythological water serpent; and a kinsperson to Jesus Christ, one of the Christian Trinity. While the speaker’s relationship with the Igbo divine spirits is one of singularity and oneness, their relationship with the Son of God is not one of oneness but that of kinship, hence the opening poem, What If My Mother Met Mary, where it can be clearly deciphered that the speaker’s mother is not really Mary, but instead relates to Mary through friendship, which happens after their first meeting at the riverbank in the same poem:

they sit for a long time

they stay friends even after their bodies spit us out

In the collection, the author skillfully uses techniques such as rhetorics and time juxtapositions to seamlessly blend different happenings of different times. The 39-poem collection, whose major themes of violence, self-harm, and abuse (both physical and mental) are explicitly explored with vivid, vulgar, and sometimes strong, blasphemous diction, is a delicious and impeccable read.

The speaker, in the second poem titled Christening, reveals themself to be “a great length,” indicating what I said in the first paragraph, of them being an Igbo mythological water goddess, Ìdémmìlí. In the poem, the author uses internal rhyme in lines like “the priests spat it back, an infected graft / smelled like a scale, they said / some slimy two-timey pagan shit” (lines 2-4), allowing the poem rhythm and musicality. Akwaeke also uses both internal and end rhymes, respectively, in poems such as Disclosure, Achilles Had His Heel, and Excommunication, thus:

no one is cruel if they are fool enough to try then they

die and what a death what a death to not be loved by me anymore the softest

gate-opener i feast on torn herbs and fat gold the wet smear of a perfect yolk

(“Disclosure”)

where the bulb of her bone

popped out of its home

(“Achilles Had His Heel”)

judas with a damp cock

left his god lying fucked

(“Excommunication”)

The author being nonbinary, it is no surprise they explore queerness in this collection. These said explorations can be seen in poems like Disclosure, in which the author basically delves into traumatic experiences; What If Jesus Was My Big Brother, in which they write:

i’ve fallen in love with a girl… he tells me about magdalene and her chestnut eyes.

These explorations do not stop, as we later see the speaker’s subsequent encounters with Mary Magdalene and ‘her chestnut eyes.’ Also, it is undeniably agreeable that Magdalene’s presence in the collection helps in the author's adamant use of allusion, time juxtaposition, and symbolism.

Throughout the collection, the speaker also says they are burdened heavily with greatness and divinity. In most of the poem, they insinuate to be some type of god, a demigod. This can be seen in the opening poem What If My Mother Met Mary, where the speaker says that their mother, June, says to Mary (the mother of Jesus) that “they never tell you what it’s like to raise a little god,” which Mary concurs to with a “triple word score” yes. The little god being themself and Jesus.

In What If My Family Came to the Hospitals, they write, “my mother weeps for them to lock me up / keep me alive / magdalene dabs blood from my skin / he should not touch you like that, she says / mary auntie holds up my mother / june, june, listen, she says / even if they die / the little gods can come back” (stanza 4). From the quoted stanza, two facts are symbolized in the speaker’s death: the sufferings and death of Christ─the inevitable experience for gods, and the Ọ̀gbánjé spirit.

In addition, in poems such as Self-Portrait as a God Who is Loved, What If Jesus Was My Brother, and What If My Father Called Jesus a Bastard, other evidence of the speaker’s godship is encountered.

Aside from the metaphorization of self, which the author does endlessly in the book, they also discuss themes such as abuse, violence, and rape, as mentioned earlier. These themes are dominant and recurring, as several poems centered on them are seen.

In Self-Portrait as an Abuser, Akwaeke rams a lot of emotions into a single poem. As the title of the poem suggests, the speaker is portrayed as an abuser. The poem, written in columns and two sides, gives the poem appeal and a sort of abuser-abusee perspective. This makes the poem a very successful one. Also, in the poem Content Warning: Everything, which the collection is named after, the speaker narrates a rape experience. In the poem, one can easily make out a plethora of graphic images—which the author warns of in the title: Everything. But one thing I thoroughly admire is that the narrator finishes the poem self-accepting and self-loving after the ball of emotions, as they end the poem with:

now here, gaze upon me! i am the fucking miracle

Inasmuch as comparing a whole book to a single poem may sound absurd, I’d liken Content Warning: Everything to Sylvia Plath’s Lady Lazarus, though not on a theme level, but on their use of time juxtapositions, biblical allusions, and sharp metaphors.

Content Warning: Everything is admittedly a sweet manipulation of language. The author’s diction propels each poem to magnanimous success, vividly painting images to a reader’s mind. These images become so real and full of life that a reader may begin to believe the speaker has physically encountered all the mentioned characters, like Jesus, Mary Auntie, Mary Magdalene, and others. However, reading the book, I wished the number of poems in the book were more than what it actually is. The author should consider writing a full-length collection in future publications.

Finally, I must write Content Warning: Everything is a very ambitious book of poetry, given that it is the author’s first publication in the genre.

Writer’s Biography

Ement Amaku (they/them) is a Nigerian nonbinary poet and storyteller currently studying for their BA in Linguistics and Languages at Nnamdi Azikiwe University. They are an alum of the Sprinng Writing Fellowship. Their work has been published in various literary magazines such as Brittle Paper and Afrocritik.