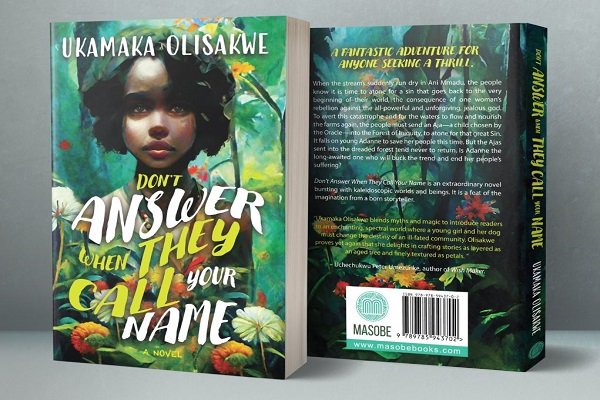

A Review of Ukamaka Olisakwe’s “Don’t Answer When They Call Your Name”

By Adeola Oke

Growing up, the only genre that truly captivated me was Christian romance. Aside from mandatory high school and college reads, you wouldn’t find me venturing into another fictional territory. I devoured these stories, often staying up late into the night, completely absorbed in the passionate journeys of faith and love. While I’ve embraced non-fiction in my twenties, Christian romance remains dominant on my bookshelf.

When Ukamaka Olisakwe’s Don’t Answer When They Call Your Name landed in my hands, it represented a different genre I had hardly explored—a fantasy adventure far removed from my comfort zone. Picking it up felt daunting. The first page, steeped in Igbo mythology and vibrant imagery, starkly contrasted the contemporary settings and relatable characters I was accustomed to. I put it down, hesitant to embark on such a different reading experience. But a few days later, I started again and couldn’t drop it until I was done reading it.

Big Father has a wife—Mother—who was eager to help and wanted to join in the farming of the yams, for she came from a race of dynamic and ambitious women whose stories traveled the universe. But Big Father rejects her help. He gave her a small piece of land far from his yam farm and said she must only cultivate female crops, like cassava and cocoyam; what mothers before her had done, and which to him were suitable for a woman. (pg. 8)

The above excerpt is where the conflict begins in the novel. I started to ask myself different questions: Why had Big Father refused to let Mother plant yam? The scene sounded familiar, and then I remembered where I had read something of that nature—Buchi Echemeta’s Joys of Motherhood and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart—I got my answer— culture. Culture has, in a way, established stereotypes in various societies, which limited women, children, and vulnerable groups to certain roles.

Cupped from the Bible, there is a particular saying that everyone now dwells upon, even if it is to cover unacceptable behavior. Women are to always submit to their husbands. People often need to remember to read the preceding verse that says men should love their wives. Because, in loving their wives, they don’t deprive their wives of anything or enforce things on them, which would, in return, make the wives submit.

Four sons,’ he said. ‘You will give me four sons. Then you can have whatever you want and do whatever you feel. (pg. 17)

Mother wanted to farm and plant yam crops, which they tagged ‘‘male crops,’’ at all costs and negotiated with Big Father. The first was giving Big Father four sons. Mother was 19 and focused on being a successful yam farmer and trader, not giving birth to children. But because she badly wanted to farm yam crops, she was happy to give Big Father four sons in exchange for yam seedlings.

Mother gave birth to four sons, but Big Father will still not fulfill his part of the bargain. For the second time, he told Mother to wait until their children had grown up and could stand on their feet for her to farm yam crops. She did, and nothing from Big Father. The third and last negotiation was her waiting for their sons to become men, ready to have their wives before she could farm yam crops. At this point, Mother realizes that Father will never allow her to farm yam’s crops.

She did not open her eyes as she pulled, as she dragged destruction to her husband’s precious farm, where he buried his mother; these grounds he worshipped and elevated and loved more than life itself… (pg. 26)

We are even now, aren’t we?’ She laughed and laughed. She was still laughing when she saw the swing of his machete. It happened in a flash. He did not allow her a second to catch her breath. She only gulped as the blade rushed towards her head. Then, a quick flash. Pain exploded in her eyes—a scream split from her throat. The world turned black. And she was falling into a deep, dark void. (pg. 28)

In retaliation, Mother destroyed Big Father’s farm, and he killed and banished her into the bad bush.

You know how we used to gather at night or stay in our grandparents’ room so that they could tell us folklore? That was the same way the story about Big Father and Mother was said to generation after generation, years after. The only thing was that it wasn’t told exactly right. Everyone was made to believe Mother was the evil one who brought calamity to the land. The story was thought until Adanne was sacrificed as an Aja to the bad bush.

It was the tenth year since the last child was sacrificed to the bad bush as an Aja to atone for our sin. Everyone knew this story: how the great Mother had sinned against Big Father, and as punishment, he banished her into the bad bush. And in that fit of anger, he declared that her children would forever atone for her sin, or they would be wiped off the face of the earth. And so, every ten years, an Aja was sent into the bad bush, and to make sure that we never forgot when it was time to perform the sacrifice, Big Father dried up our stream, creating a Plague of Famine, until an Aja was sacrificed. (pg. 37)

Adanne and her little brother and friend, Obi, went to the bad bush. Although it is called a bad bush, the writer didn’t portray it as dark and evil. The image of the bush in my head is all green, a small city full of plants that could talk and animals that could walk and speak like humans. I love what Ukamaka did unconventionally with the bad bush. Also, at first, I thought Obi was human, but I later realized it was Adanne’s dog.

Nothing can cut through this thing,’ Mother said. ‘I tried everything.’ ‘Except for the machete,’ I said. She nodded and stepped back, putting more than five feet between us. ‘Now, please, go ahead and cut the cursed thing. (pg. 212)

Everyone in the bad bush also believed that Mother was the villain. However, after a lot of back and forth, the true story of her heroism was out. Through the help of Adanne’s father and other people in the bad bush, Adanne used Big Father’s machete to cut the unusual metal lock he used to keep water from running.

The writer did an excellent job of creating a good image of every scene in the book. The setting, myth, and mystery used appeared natural. For a second, you might think you are watching the timeless ‘Koto aiye’ or ‘Saworo Ide.’ I also love how the writer code-switched, letting the native tongue drive the taste of the stories.

Another thing I deduced from the novel's final part is how unity can bring a lot of achievement. They could not achieve anything when they were working against themselves in the bad bush. But the moment they knew the truth and united, they could work against the ‘real enemy’ and conquer.

Olisakwe masterfully weaves Igbo mythology into the narrative, creating a vibrant tapestry where spirits and ancestors whisper alongside human characters. The lush descriptions of the ‘bad bush’ transcend typical forest imagery, transforming it into a living, breathing entity—a character itself that challenges perceptions and nurtures growth. Each scene unfolds with cinematic clarity, transporting the reader into the heart of Adanne’s journey from the oppressive village to the transformative depths of the forest. Through Adanne’s defiance and self-discovery, themes of tradition versus individual agency, environmental responsibility, and the power of storytelling resonate powerfully. The book’s exploration of these themes feels organic and deeply woven into the fabric of the narrative, never overshadowing the captivating plot or the characters’ emotional journeys.

Stepping outside my comfort zone with Don’t Answer When They Call Your Name wasn’t just about discovering a new genre and challenging my own perspectives. Witnessing Adanne’s journey to defy cultural norms and the hidden truths unearthed resonated deeply, encouraging me to critically examine societal biases even within my familiar ground. This book isn’t just a fantasy adventure; it’s a thought-provoking exploration of tradition, gender roles, and the courage to rewrite narratives. If you seek a book that will transport you to a vivid world while prompting introspection, step into the ‘bad bush’ alongside Adanne. You won’t regret it.

Writer’s Biography

Adeola Oke is a creative powerhouse weaving words into stories, poems, and engaging content. As a Communication and Language Arts student at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, she fuels her passion for language and empowers others through writing. She is a 2020 alumna of the Sprinng Writing Fellowship and has been published in publications like Spur Nation Magazine, Teens with a Difference, Sparkle Writers Hub, and ZenPens. Adeola's voice has resonated with diverse audiences, and as the author of the Live Each Day With A Poem (LEDWAP) Anthology, a 100-poem exploration of love, friendship, and more, her work finds beauty in everyday themes.

Beyond this, Adeola runs a personal faith and lifestyle blog at "Adeolaoke.wordpress.com,” with over 60 published posts. Here, she educates, informs, and entertains, inviting readers to share her journey.