Foreword by Chideraa Ike-Akaenyi

Writing as writing. Writing as rioting. Writing as righting, On the best days, all three. - Teju Cole

What does it mean to create?

Why must you stay true to your art?

What should inform the art-making process–whims, a desire to reinvent, a flexing of prowess on the page?

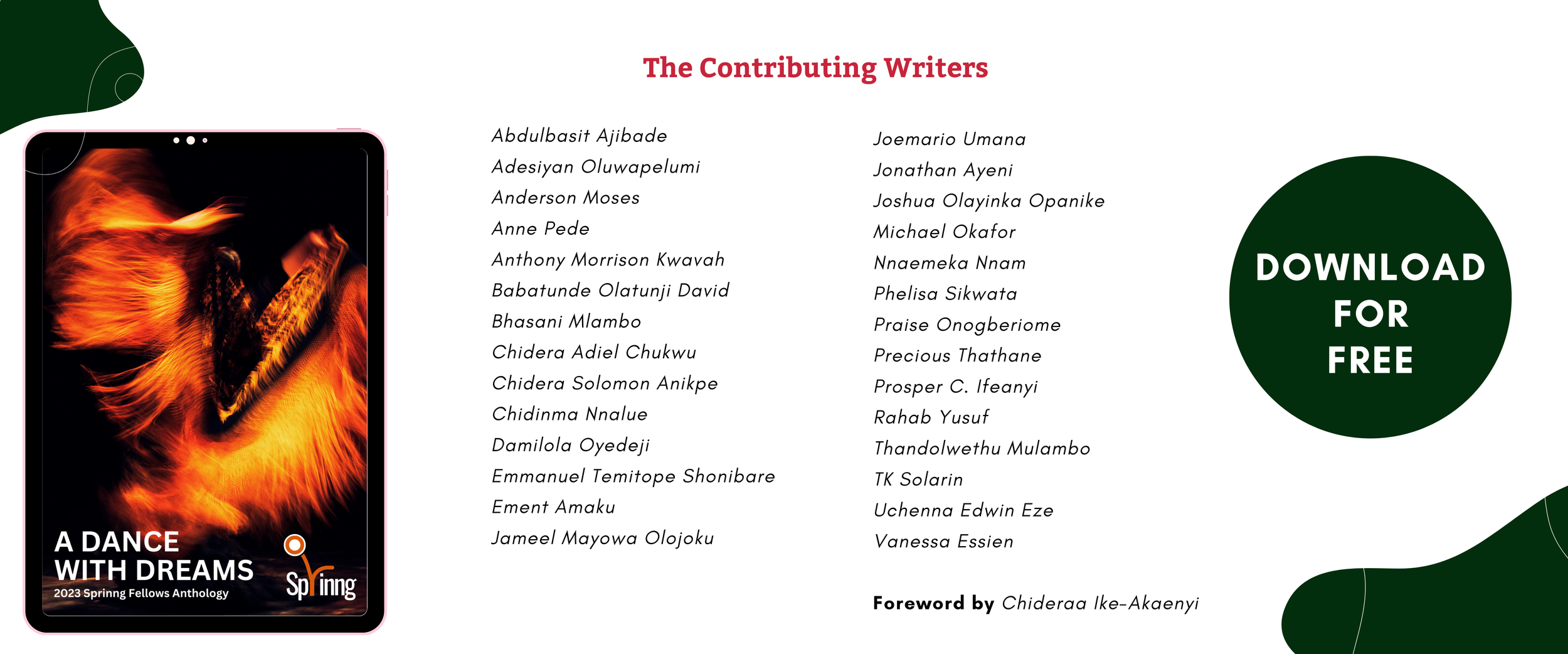

The textured writing in this anthology answers the above and more. Here, you will find legion–the forlornness that is being in a world that drains you of all individuality, a celebration of the little pockets of joy in despair, a luxuriating in the simple things that matter, a protest against harrowing living conditions, against oppressive governments, against harmful dogma.

From introspective essays that draw from rich traditions in literature and hip-hop culture to stories that make you question brevity and poetry that asserts wholeness, A Dance with Dreams takes you through the long, winding streets of Nigeria and Ghana to South Africa, impressing upon you the manifold nature of its background. Michael Okafor’s Volo te Salvum Facere is haunting in its portrayal of life in war-torn Northern Nigeria. Precious Thathane’s All Backstreets Lead Home teases with its tale of a character questioning memory. Phelisa Sikwata’s Nina is a heartfelt ode. T. K. Solarin’s Don’t Call Her Name is whimsical in that it tells a story with a postscript.

For the writers here, words are not marks on parchment. They are living things, tools for making things happen. Words are active catalysts for reinventing, mortar to build new worlds, and scalpels for dissecting harmful philosophies. For B. O. David, he “make[s] words into knives and carves the best versions of [his] father and [him] all within [him]self.” For J. M. Olojoku, writing “is a journey of dissociation, where [he] severs [his] true self from the self that was made. It is, for [him], a ceremony of birth, a renaissance.”

It is refreshing to see that the writers here are as aware of the present as they are of the past. Anderson Moses echoes this, “Words are big things, the foresight of the distant past, the coming future, and the things that surround it.” This centering is evident in Prosper Ifeanyi’s essay, where he situates his art in literary traditions spanning decades. His work is a reminder that it is not enough to revel in the novelty of the present but also to acknowledge how much of the past is present in it.

In an uncertain world, where freedom is the preserve of a few, it is refreshing to see art that dares to question. It is delightful to see art that is obstinate about creating new or alternate realities with shards from dreams carried in bellies for too long. Here, you will find strong voices, unsure voices, voices insisting that you share in their daring to dream and hope without reserve. In Jonathan Ayeni’s words, in A Dance with Dreams, you will find “testaments to the human capacity for introspection and transformation.”

Chideraa Ike-Akaenyi

Okpuno, Nigeria.